Balanced Funds

Are the Days of ‘Cautious’ Balanced Funds Over?

What’s in a name?

Well, in a manner akin to selecting one’s clothing, there’s no ‘one-size fits all’ solution when it comes to investing. Unlike cartoon characters who might wear the same outfit on every occasion, you need to dress suitably for the prevailing conditions outside.

For more than twenty years, the asset management industry has relied on a similar approach when trying to address an investor’s risk appetite – a standard, static, fund allocation of equities and bonds (whether that be 20% equities/80% bonds, 40/60, or the bellwether 60/40 balanced fund). The same funds, it should be noted, which are sometimes labelled as ‘cautious’, ‘defensive’ or ‘low risk’ in the fund name, or used as the risk classification in the fund’s investment profile.

While there’s nothing wrong with these actual portfolio weights, or the use of government bonds in general, with inflation still untamed and interest rates rising these last eighteen months, this approach has struggled. During this time frame, bond volatility has surged while returns have been negative.

Inflation and Interest Rates

It’s hard not to imagine reading about the markets these past 18 months without inflation being a focal point. As a consequence, the goal for most central banks recently has been to get inflation under control.

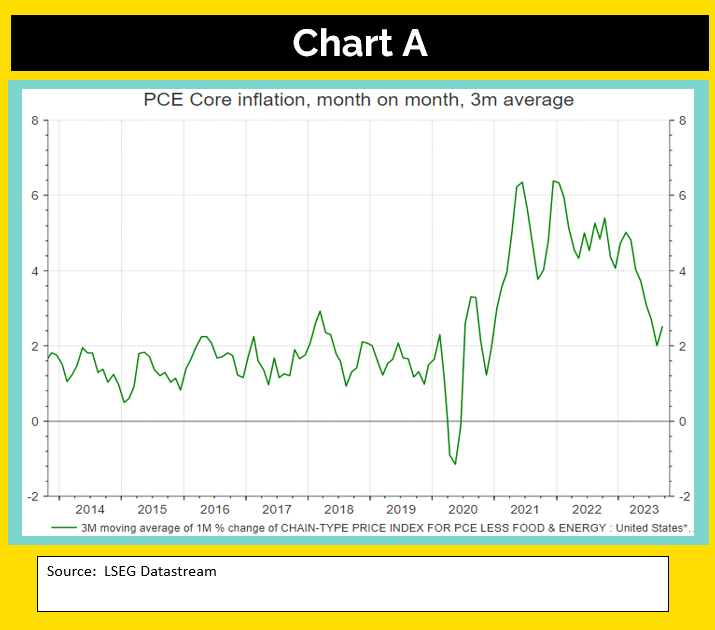

For now it would appear that inflationary pressures have receded, particularly in the USA, that is, assuming the Federal Reserve Bank’s preferred measure of inflation is Core Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE). Over the last few months, the rolling 3-month moving average has dropped to 2.5% from a peak of 6.4% in December 2021 (as shown in Chart A).

Is it time for the Fed to declare victory? Alas, most likely not. While the ‘Fed’ may say that it’s data driven, it often feels like its reputation dependent instead. Having mistaken the inflationary surge of 2021 as ‘transitory’, the Fed’s rhetoric continues to remain rather hawkish. With the US economy remaining robust, the debate between a soft or hard landing seems less relevant, with interest expectations having migrated to a ‘stronger for longer’ perspective.

In the UK, expectations as to the level at which interest rates will peak have certainly come down significantly. However, what we are not seeing is any expectation, on either side of the Atlantic, of when rates might be cut.

Bonds

For bond investors, there have been a number of unwelcomed developments recently.

It’s probably fair to say that most investors have only experienced a bond ‘bull’ market. For decades, fuelled by increased globalisation, improvements in technology, low inflation, and falling central bank base rates, the environment has been positive for bonds.

This environment was further ‘turbo-charged’ following the global financial crisis in 2008, and the COVID crisis in 2020, as central banks used every weapon in their arsenal to support the global economy. The use of extraordinary measures, such as quantitative easing (QE) and yield curve control, helped keep interest rates at extremely low levels.

Governments/Central Banks became both the issuer and also the largest buyer of their own bonds. Bonds became the safe, low volatility way to mitigate equity risk. For market participants, weaker economic data was seen as bullish for bonds (“more QE please?”), despite rising government budget deficits. This backdrop couldn’t have been any more supportive for a 60/40 strategy.

That all changed in 2021 and 2022 when inflation returned, interest rates rose, and a monetary policy of QE morphed into QT (quantitative tightening).

Developments over the last six months suggest a more fundamental problem is now emerging. Inflation is falling, the peak in interest rates may be on the horizon, and short-dated treasuries and gilt yields have fallen back modestly.

Yet, at the long end (10 years+), yields have kept rising. US 30yr government yields have hit levels not seen since 2007, and in the UK, not since 2004 (Chart B). It’s the same pattern across Europe.

Investors are demanding higher interest rates on long-term government debt, which by definition, means that they regard governments as a higher credit risk. Why?

In my first economics lesson at Leeds Grammar School, in September 1981, I was told that the price of any good or service was determined by the interaction of supply and demand. And that applied to government debt as well. Back then, the budget deficit (called the PSBR) was the key economic data point – it was the measure of gilt ‘supply’.

Yet, when it came to bonds, for 30+ years it seemed ‘supply’ didn’t matter. In the great gilt bull market, and then with QE, supply remained missing from the equation when determining gilt yields.

Now, concerns over supply as a factor have returned … and politics have changed.

Whether it’s a result of COVID, lockdowns, or furloughs, we are in a political period in which it’s all about spending. No matter where you might sit on the political spectrum, today’s politicians seem to be singing from the same hymn sheet when they talk about ‘investment’, ‘long term investment’ or ‘green investment’. More borrowing!

The UK budget deficit is running at £135bn, about the same as during the bottom (January 2010) of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 (Chart C). Up to this point in time, there has been almost no appetite from politicians to address this in a meaningful way, either in the UK or across the channel. It’s a mix of Jean-Claude Juncker (“we know what we need to do, we just don’t know how to get elected afterwards”) and St Augustine (“lord, make me virtuous, but not just yet”).

While it’s a little better in the US, with a robust economy operating at near full employment, they are still running a huge deficit.

Yet, as early as the late 1990’s, both the UK and the USA had budget surpluses.

For bond investors it seems the ‘bad’ penny has finally dropped. Government bond supply (care of budget deficits and QT) is huge, and politicians are unlikely to tackle it. As a result, long-term yields have moved much higher.

Keep in mind, the bond market isn’t just government bonds. But it is over half of it, and therefore a significant driver of bond market returns.

Balanced Funds

In this environment, bonds are sadly adding to overall risk, not detracting from it. For investors close to retirement, who may have invested even in a 20/80 portfolio with the objective of protecting their capital, they may be dealing with a very uncomfortable and surprising reassessment of their retirement plans.

Over the last three years, the weak performance of bonds within these funds/portfolios has contributed to overall investment returns that lag even global equities, AND with similar levels of drawdown (Chart D).

For now, bonds remain highly volatile, and they are certainly not behaving in a way expected, based on recent times.

Portfolio Construction

All of this is not to say that bonds are not an important part of portfolio diversification. However, there are times, like the current market environment, when investors must look beyond a generic passive allocation to government bonds in their portfolios to help possibly insulate returns. There are opportunities to be found within the bond space but investors have to be selective in where they allocate capital.

An assessment of opportunities available might also include a review of correlations across all asset classes, to see the role each plays in the portfolio’s overall risk/return profile – not simply from a traditional sense of bonds acting as a ‘risk-off’ (i.e. downside protection) allocation, but whether they could be appropriate to allocate from a ‘risk-on’ (return) perspective.

Allocation approach – one possible strategy is an allocation to some of the sections outlined below, to provide some opportunities while helping to control risk levels.

1. A barbell approach to duration (i.e. interest rate risk). For example, a combination of short-term and long-term exposures could prove to be beneficial and may help manage risk better in this current market. There may be an opportunity for longer duration bonds to provide a real yield at these levels, with the added benefit of some downside protection should there be a reduction in future interest rates. However, this approach may increase the sensitivity of a portfolio to interest rate risk, so a combination of longer duration with shorter-duration bond exposures could help mitigate this risk.

2. Size Matters. Understanding how each asset contributes to overall portfolio risk is important. When trying to take advantage of the current market opportunities, one way to achieve sufficient levels of risk is to balance riskier assets with less risky assets, to use as a control measure. In times where correlations are high, determining the correct allocation sizes is imperative to ensure the overall portfolio risk is controlled appropriately.

3. Liquidity. It is imperative that investors understand how parts of the fixed income market, and the funds that that have allocations to those parts, might behave should there be a liquidity crunch, such as what was witnessed during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008.

4. Yield levels. With elevated interest rates for now, and rate cuts looking increasing unlikely, money market funds can offer competitive returns with minimal (but not zero) levels of risk. In addition, yield levels have increased across the fixed income space, so there are opportunities to pick up good levels of yield. However, it is worth remembering that yield is compensation for the level of risk taken; risks generated by higher yielding assets must be understood and controlled.

5. Bond sectors/sections. Certain sections of the bond market, for example the credit of high-quality firms, may provide some good opportunities at these yield levels. These companies are likely to generate high cash levels, have good balance sheets, and are less exposed to re-financing risk when their debt matures. The bonds issued by companies such as these should provide good yields but with a much lower default risk. Again, being selective could literally pay dividends and provide some diversification from the government bond passive funds.

6. Trading strategies. There are a number of dynamic active funds, such as strategic bond strategies, which offer the scope to ‘flex’ bond exposures across the bond universe as market conditions evolve. Some of these funds can easily shift between different parts of the market, different sectors, risk ratings and levels of duration. An active fund with a fund manager who can navigate through this type of environment well could offer diversification benefits in the fixed income allocation and help improve the overall risk profile of the portfolio.

7. Real assets. Outside of the fixed income space, commodities (e.g. oil, gold) may offer true differentiation from equity and bond returns, as well as possibly help to protect investors on the downside if geopolitical risks should increase. Recent events have seen positive gold returns against a background where most asset classes have seen negative returns.

While bonds could well become attractive again from a tactical perspective, the days of a passive, uncorrelated 60/40 strategy seem unlikely to return in the short term. Falling inflation, combined with the possibility that interest rates have peaked, has not provided the scale of relief that many had hoped for in the bond markets.

What’s in a name?

Well, for most balanced funds, perhaps it’s devising a better label when it comes to describing their performance in this environment.