China - the 21st Century Poster Child of Growth

Whatever happened to China?

This was meant to be their century, one where their economy would become bigger than the USA’s, with huge political and economic ramifications for the rest of the globe.

However, it doesn’t feel like that anymore. Whilst this might not be the Soviet Union circa 1985, in which nobody back then (and I mean literally no-one) predicted its demise several years later, China is entering similar uncharted territory.

We know that China’s macro data should be issued with a health warning. Their GDP number, for example, comes out quicker than the US one and is never revised. It’s a political statement of intent, not an independent economic measure of activity, and inconvenient data such as youth unemployment is no longer published.

So where do we look to see what’s really going on… and just how bad it is?

Given China’s economy has been built on the twin pillars of exports and high levels of domestic investment, particularly in the residential market, let’s start there

Housing

For an economy literally built on residential developments, residential (new) build rates are a good place to begin. When even the ‘supposedly better’ developers such as Country Garden, which recently announced record losses, are facing oblivion, then we know there is a real problem.

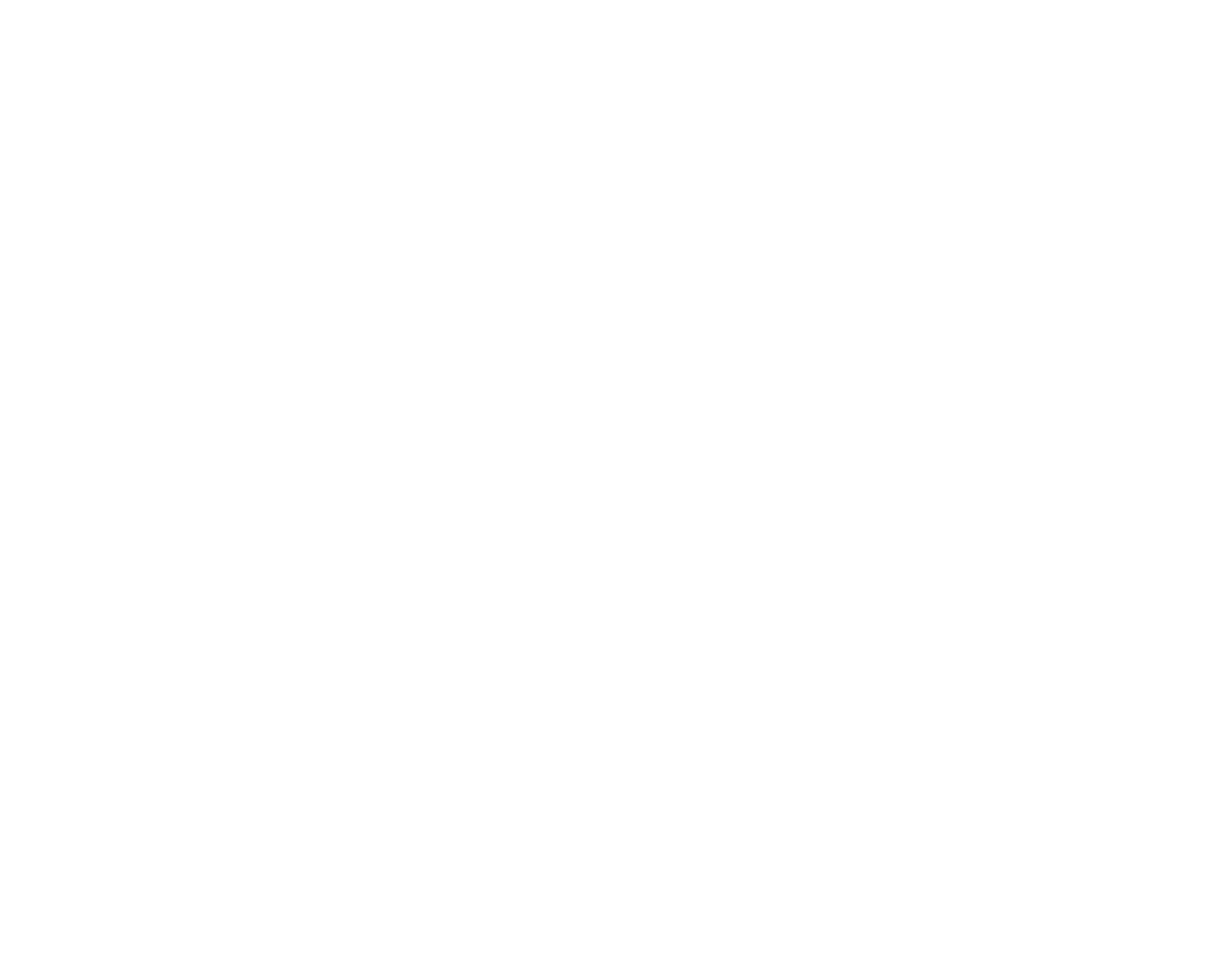

Chart A shows the official cumulative YTD square footage build data on an annual change per month, over a two year period.

Note - the ‘gaps’ in the chart are because China does not release monthly data for Jan/Feb due to variances in the New Year date.

The collapse in activity levels is astounding. July 2023 saw build rates 60% lower than two years previously, and this collapse in activity has been persistent for the last three years overall. This is worse than the US housing collapse of 2008/09, and it shows no sign of ending.

Not only is the sector hugely indebted, but it is also intertwined with the debt and funding problems of China’s regional governments.

Exports

What of the other pillar of China’s economic story – exports?

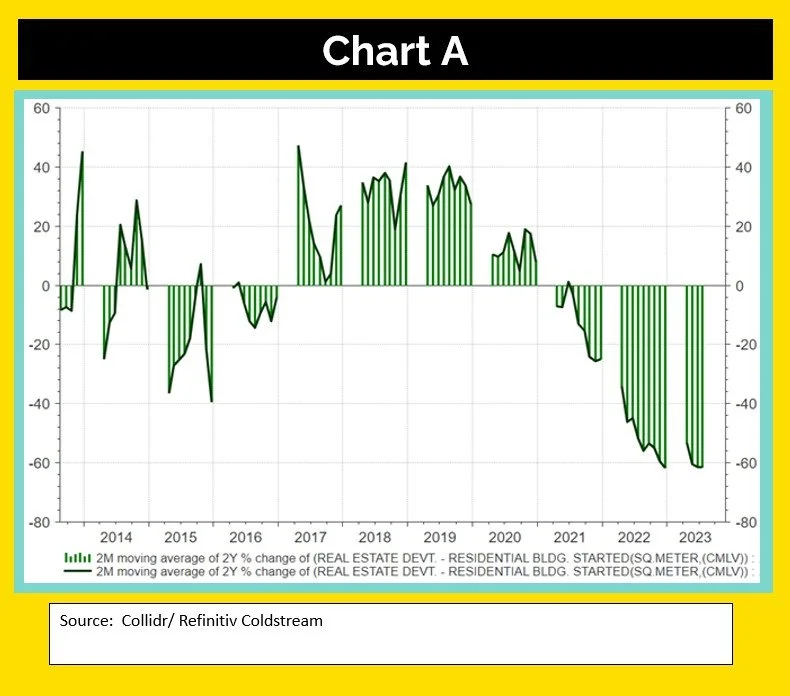

Well, it appears that their biggest export market is abandoning them. Despite the robust performance of the US economy, China’s exports to the US have fallen sharply. A number of factors are at play – more countries (e.g. Bangladesh) are undercutting China on costs, subtle and not-so-subtle actions by the Biden administration to cut back on Chinese imports in certain areas, as well as an overall cooling of Sino-US relations, not to mention a post-COVID shift in supply chains from ‘just in time’ to ‘just in case’.

Chart B shows US imports on a rolling 12-month, annual change basis. It’s currently running at -15%, which is worse than during the period of the global financial crisis of 2008/9. This data shows a structural, rather than a cyclical decline. This isn’t due to a lack of US demand for imports, but an active decision to reduce imports from China.

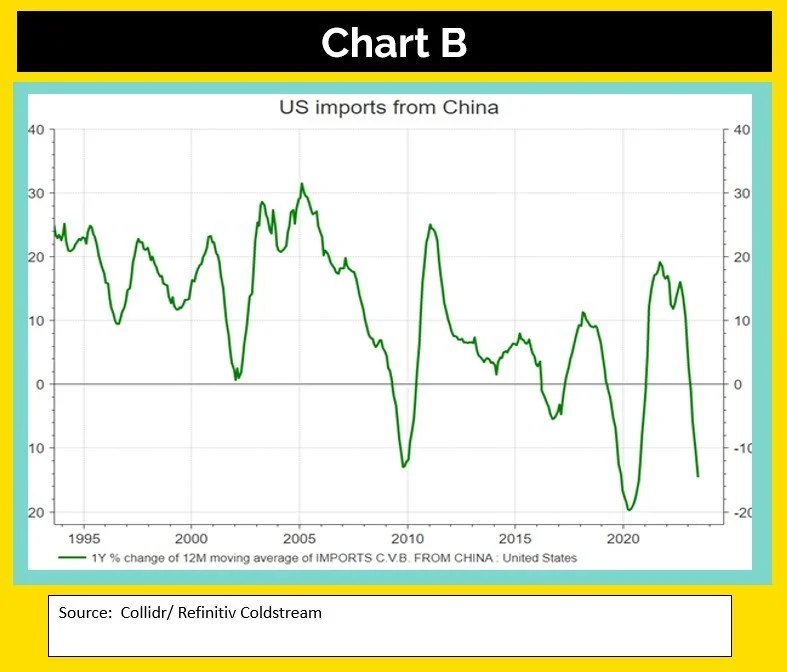

As mentioned before, a lot of China’s data is unreliable (for example, confidence surveys), artificially generated (GDP) or restricted/unpublished (youth unemployment), or often a combination of all three. However, there are some data points which do offer us a glimpse behind the curtain. Cement is one such (simple) example. After all, cement production for a ‘vibrant’ economy as China should hopefully give you a sense of what’s really going on.

If you look at Chart C, the annual change of cement output, overlaid to the ‘official’ GDP numbers, then the days of double-digit increases are long gone. Now its double-digit declines. It would appear no one has told China’s state statisticians, the ones who put the GDP numbers together, of the collapse in US exports and property construction.

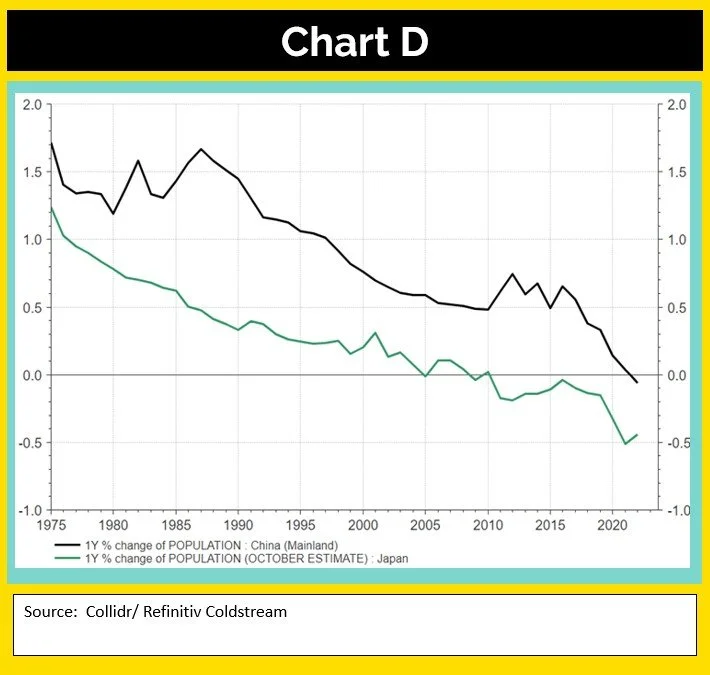

One final chart – China is getting old.

Crucially, it’s getting old long before it became rich (GDP per capita is still very low), and not before it also got into debt. China’s population is falling… but without the middle-class incomes and social security safety net of other western nations (for example, China’s neighbour, and often adversary – Japan) to help them.

We saw how the demographic time bomb presented a huge challenge to Japan, one that is taking decades to overcome, and it’s going to be an even bigger task for an authoritarian state such as China.

With the huge debt burdens of their state-controlled enterprises, and the reluctance of Chinese consumers to dip into their savings (with no social security in China, savings are seen as a necessity), it’s probably not surprising to see sharp falls in Chinese consumer and business confidence. China’s demand, or lack therefore, is a concern.

This isn’t just a decision over direct equity or bond exposure to China. The global economy has become used to a robust Chinese economy, particularly in times of stress (such as during the global financial crisis of 2008/09). Going forward, a more structurally challenged China could have profound implications for the rest of the world, whether in the short term that is exporting deflation as PPI inflation turns negative, or the impact on global trade from a weaker currency.

With a structurally challenged and imbalanced economy, some very difficult decisions lie ahead. But, given the resources at their disposal, China still has the potential to recover from their current difficulties over the longer term. One should never discount the second largest economy in the world. It’s up to China to find the right path to overcome these challenges.

Over to you, President Xi.